SECTIONS

– Top of page

– Biography

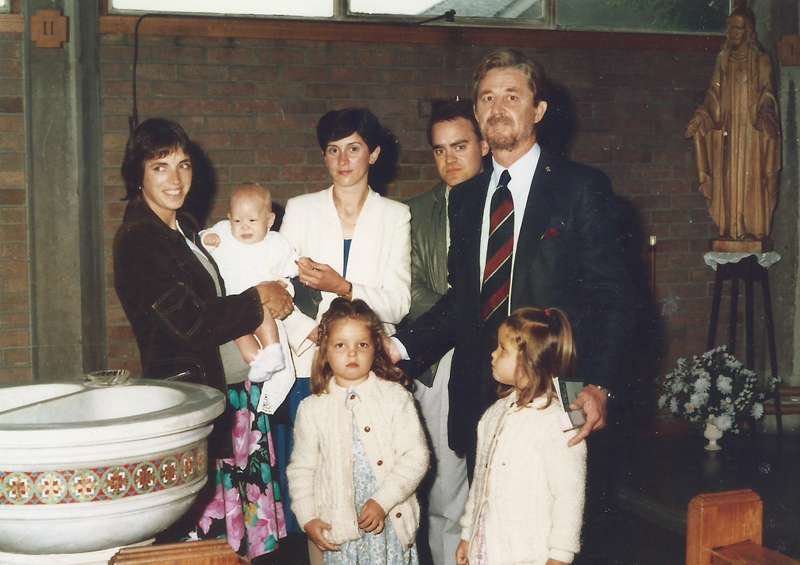

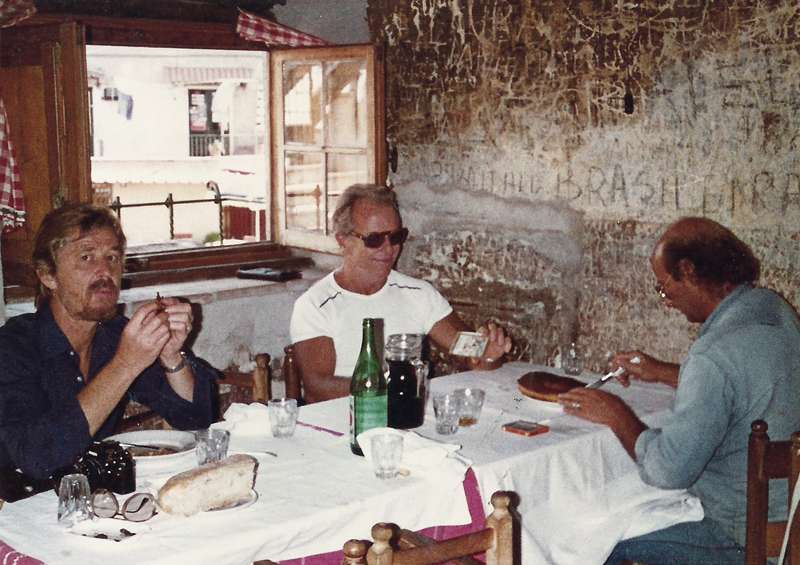

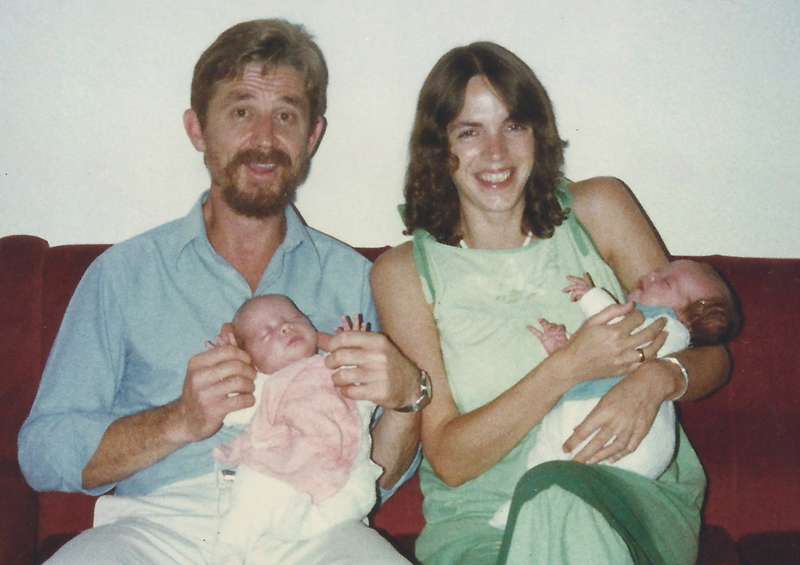

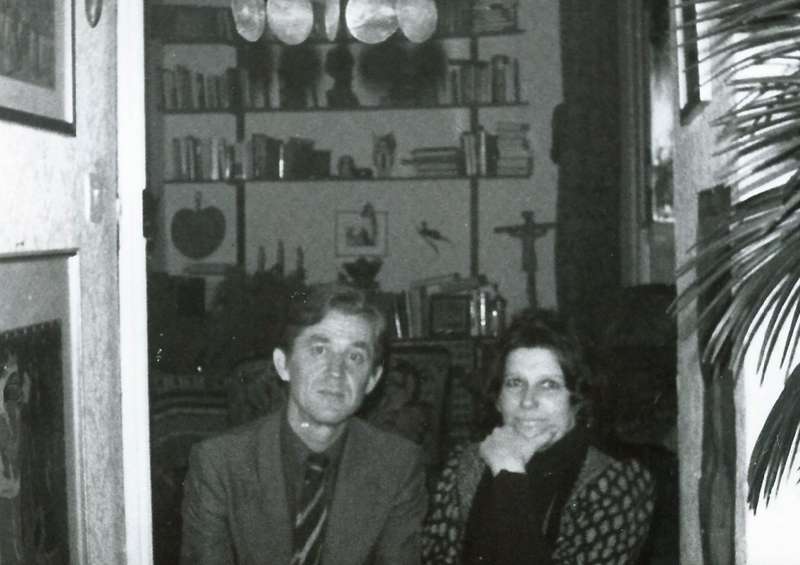

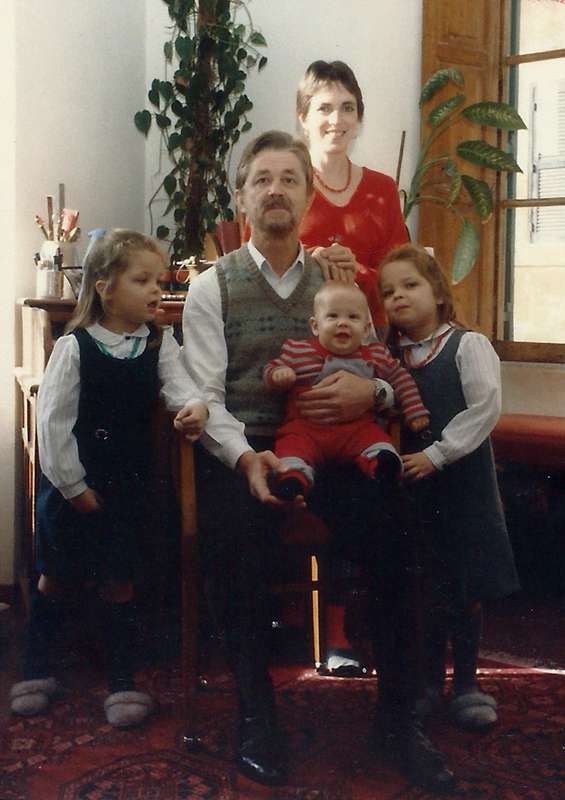

– Photos

– Songs

– Donate to charity

LANGUAGES

– English ![]() (selected)

(selected)

– Italiano ![]()

Menu

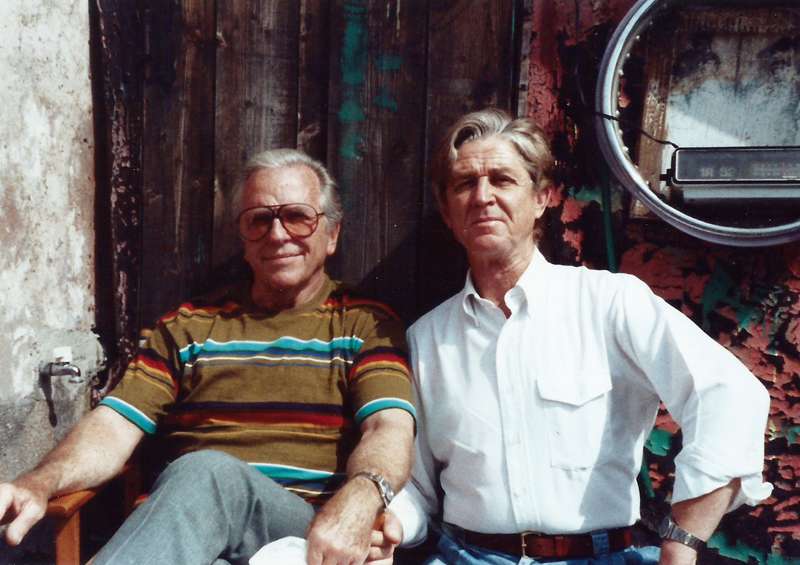

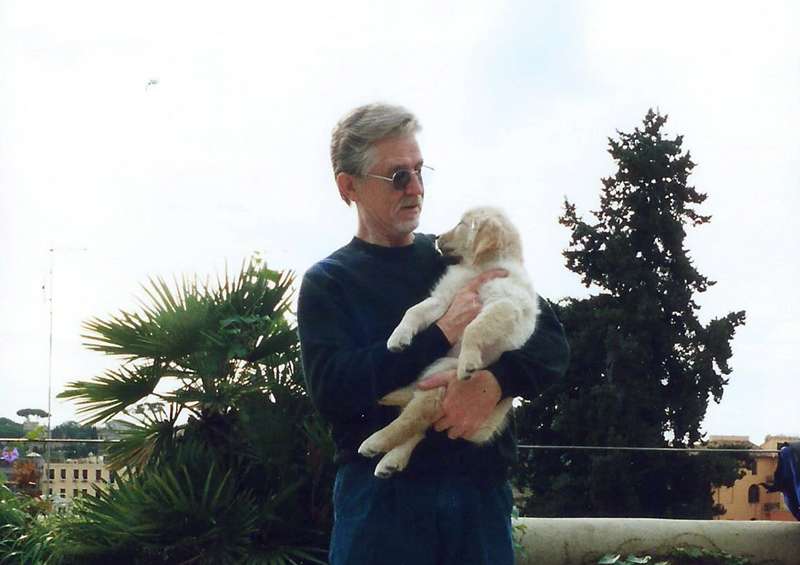

Gary Patrick Gainsforth

Father, husband, uncle

14 August 1937 – Fremont, Nebraska USA

18 January 2022 – Rome, Italy

forever in our hearts

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate.

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer’s lease hath all too short a date.

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimmed;

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

By chance, or nature’s changing course, untrimmed;

But thy eternal summer shall not fade,

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st,

Nor shall death brag thou wand’rest in his shade,

When in eternal lines to Time thou grow’st.

So long as men can breathe, or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

(Sonnet 18), William Shakespeare

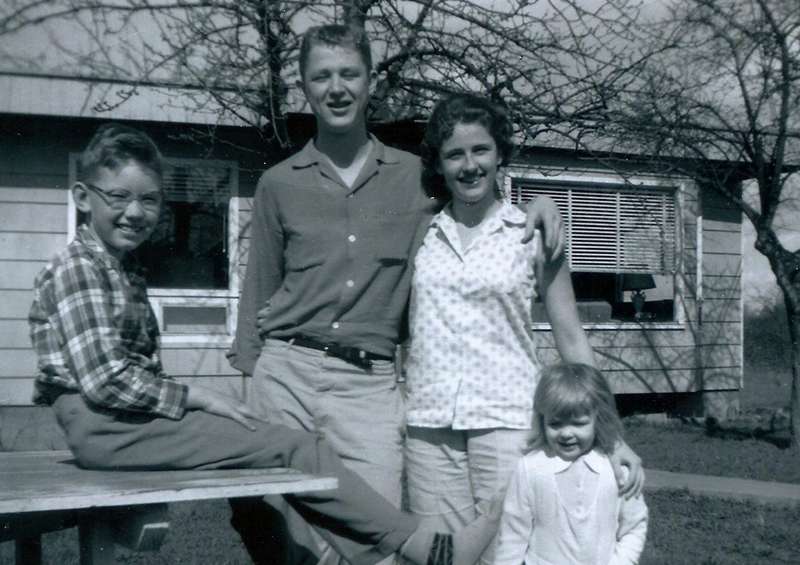

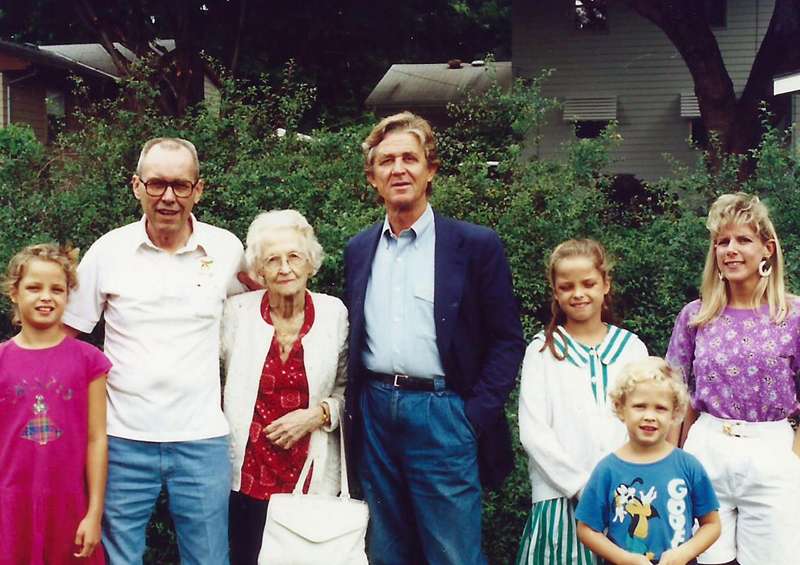

My father was born in August 1937 in a white wooden house in Fremont, a town of 25,000 inhabitants in Nebraska, in the heart of the United States. Here, in the Plains, the land is flat and corn and wheat crops stretch as far as the eye can see. Houses dot the landscape along the railroad that crosses Nebraska from east to west, where small towns are built on grids as regular as the borders of the state. The silence is broken by the passage of freight trains. Nebraska is a fly-over state, no one stops there. In the mid-nineteenth century fortune seekers looking for gold crossed Nebraska on their way to California, because here, as the signs read, the West begins.

“See that tree. I used to run up it when your grandfather took off his belt” my father told me on our last trip there. My grandfather, the grandson of Irish emigrants, worked for the gas company on road construction sites. If dinner wasn’t ready when he returned from work, he would jump on the newly made beds in his muddy boots in protest. My father was the fourth and last child, he was “spoilt rotten”. My grandmother was the daughter of German emigrants; she took in laundry from the neighbourhood. “She never wasted a crumb. When she had enough she would make meatloaf with crops from the garden”. They were poor. “Your grandfather thought about money all the time. He was very careful with money, very stingy”. Nobody had any money in Nebraska during the Great Depression. By the time my father was born, the Depression was a thing of the past. But the economic crisis, like a war, had marked the character of those who had experienced it. Curiously enough, it also marked my father’s character because, in opposition to his parents, he decided at a very young age that he would never worry about money – at least no more than was strictly necessary. And so it was. “When I had it, I spent it; when I had none, I didn’t”. He never saved a dime.

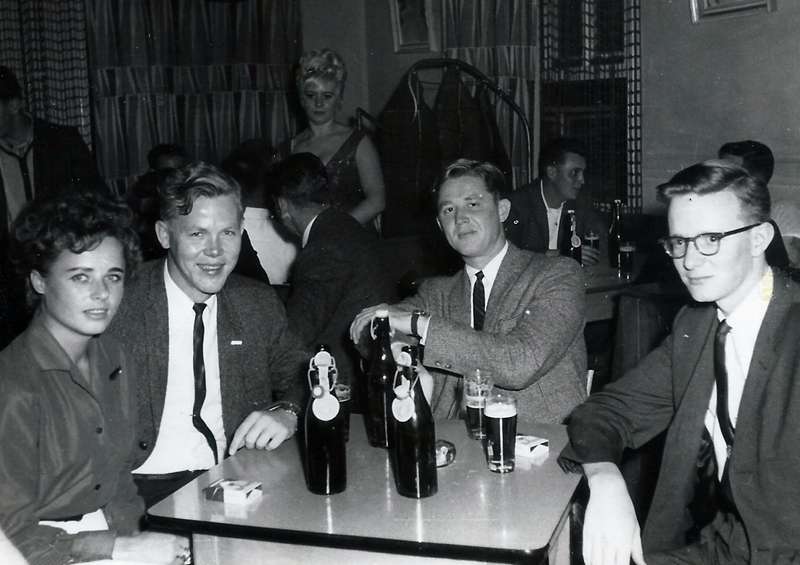

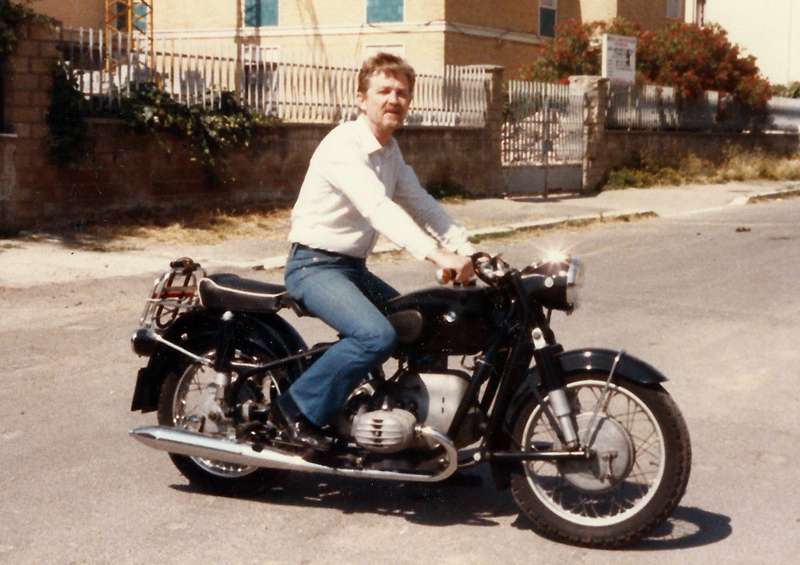

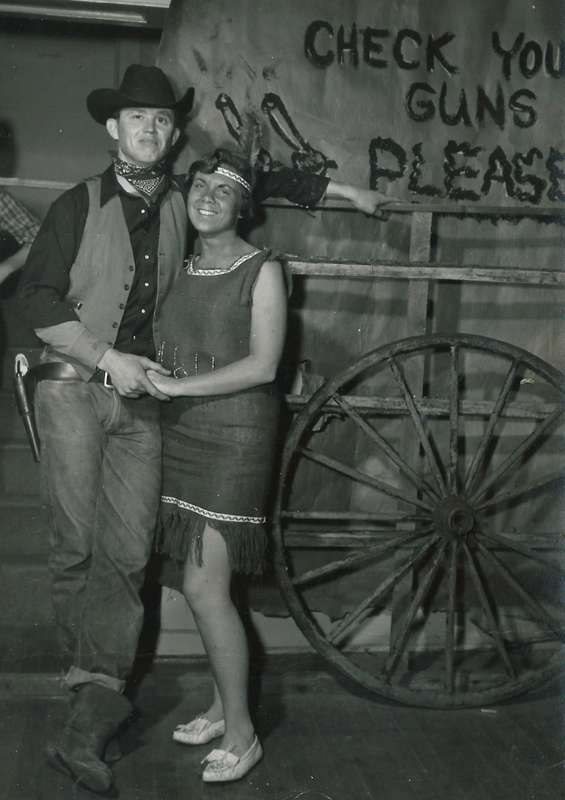

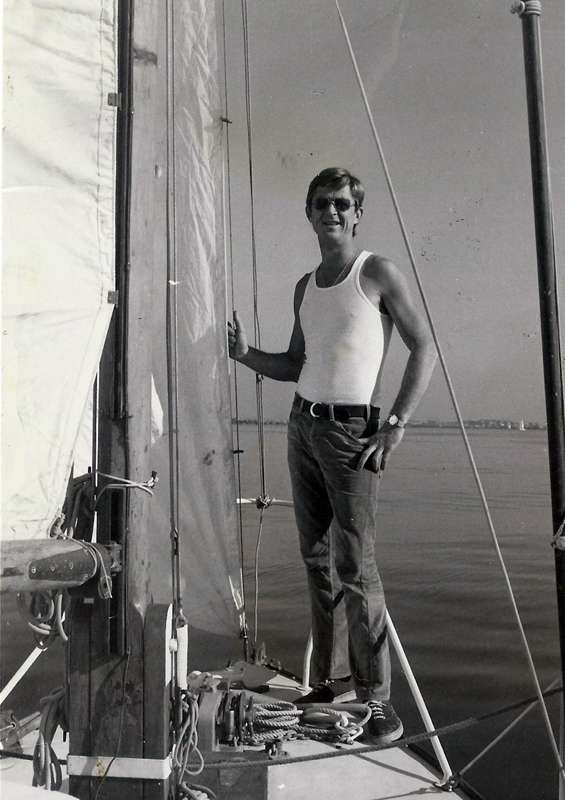

At the age of fifteen, after two summers spent working in the cornfields, he bought a motorbike. At sixteen he hitchhiked to San Francisco and went to the movies. At seventeen he started working at the gas pump. He left when he was nineteen, straight out of jail, and never came back. In fact, he sometimes denied being born in Fremont. While still a minor, he was sentenced to one year in an adult prison. The others got off with eight months in a juvenile reformatory. Together they broke into a hardware store at night and stole some tools. They were for a friend: “He couldn’t walk properly so he couldn’t find a job. He wanted to be a mechanic, he could start a small business but he didn’t have the money to buy the tools, so we stole them”. They were caught. My father was identified as the mastermind of the operation when in fact he had only been a lookout, but he was the most impertinent in the group. When he had served his sentence and finished parole Reverend Shaw’s son, (“a thief”) told him that the Reverend himself, the one who held mass in town, had insisted with the judge that he order an ‘exemplary sentence’. My father never spoke of that year in jail, but he must have feared for his life because he tattooed his name with a ballpoint pen on his left calf – in the summertime we would see him walking around in white socks pulled up to his knees. He had certainly been a hothead, but at nineteen he was a dangerous criminal, in the words of Reverend Shaw. He left Fremont with twenty dollars in his packet, all that my grandmother had managed to put together. He hitchhiked to Oregon, where one of his sisters had moved with her husband. “They were poor, they could barely feed the kids”. He loved Oregon and the wild Oregon coast, “entirely public, from south to north, since 1911” – the year the state decided to protect the coast from construction. He found a job working nights at the hospital, after that he worked as a reporter for the local newspaper, and he enrolled in university. He learned Shakespeare’s sonnets by heart and, while everyone else was dancing to rock ‘n roll, he listened to classical music. He left before finishing university. Free, almost an adult, he wanted adventure and to see the world.

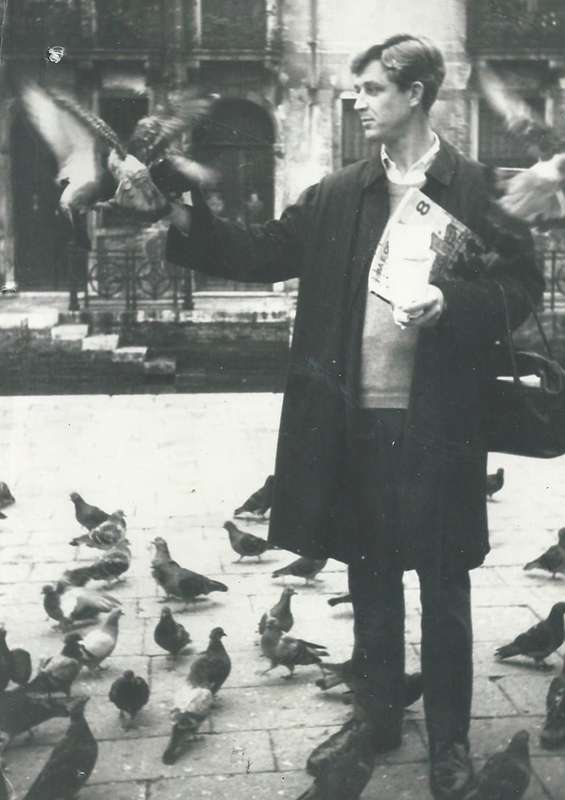

In 1963 my father decided to go to Europe with a friend. There didn’t have a plan, but they had a car, a white Jaguar with red leather seats. Which, they soon found out, was no good for travelling. They sold the car and bought another, an English make, smaller car, perfect for travelling. They headed for Panama. My father had 300 dollars in his pocket. They stopped in Las Vegas, drove through the Grand Canyon and arrived in Mexico City. My father went to see a bullfight while his friend puked his guts out over something he had eaten. “We had stopped shaving by then and had long beards.” Dad always cared a great deal about his appearance – but I suspect he really learned the value of ‘keeping up appearances’ in Rome. In any case, when they arrived in Guatemala with the intention of staying with friends, he refused to meet them in that state. Instead, he went to a bar where he found out that an American coup was in progress. Some guy asked him if he was American. He looked at a poster on the wall with a British flag and quickly replied “no, I am British”. The guy, a communist lawyer, explained to him the political situation in the country and the nature of the American intervention. There was a curfew. The guy took him to a hotel where my father woke up the next morning bitten by bed bugs. This was one of two encounters – the lawyer, not the bed bugs – my father had in those years that changed his political view of the world. It was through that conversation, he told me, that he began to see things differently.

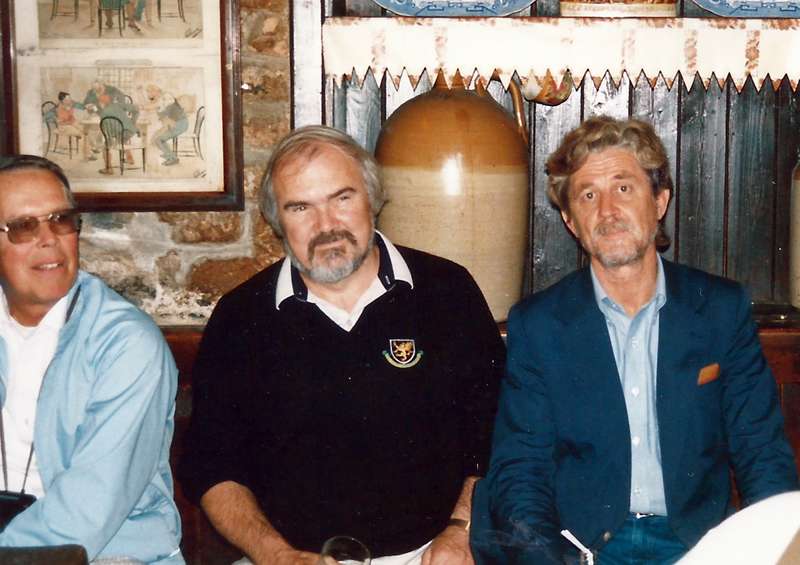

In May, he and Dell, his friend, arrived in Panama with a vague plan to find work on a ship sailing to Europe. They sold the car and went down to the port to talk to some sailors. My father pulled one of his usual stunts. Dressed in his best clothes, he told Dell to walk behind him holding an umbrella over his head as if to protect him from the sun. He told this story with a self-satisfied grin, but I honestly miss the point of him pretending to be rich when they were just looking for work. In any case, there was no work on the big ships. They would have to try the private boats. The sailors pointed to a yacht moored nearby. The captain took them on board. It was John Wayne’s yacht, and my father had just become his bartender. They stopped in Costa Rica and the West Indies, my father had a great time and ate “like a pig”. They arrived in Lisbon on July 4, 1963. John Wayne gave my father and Dell 300 dollars each and has his chauffeur drive them to the train station where they took a train to Paris. But they got off before getting there: they wanted to see Madrid and the Basque Country. From there they hitchhiked, then they got into an argument. My father had no money. Having parted ways with Dell, dad hitchhiked to Frankfurt. A few days later he had a job and new friends, and was sitting in a restaurant eating “live!” oysters. From there he went to Innsbruck: he wanted to see the Winter Olympics – it was 1964. Then he lived in Paris and met Jim, ran out of money again, slept on a bench and went hungry for a week. Jim, who in the meantime had gone to Rome, invited him to join him: dad could stay with him, he was teaching English and had rented a house. Dad took a train. His first impression of Italy is of being ripped off: he had ordered a coffee in a bar in Florence and was outraged when the waiter gave him a minuscule amount in the tiniest of cups – an espresso. At Jim’s place on the Janiculum he found a book lying on the kitchen table; in it was a description of Rome that his friend had copied in the letter he had sent him inviting him over. Emma thinks it was a letter from, or to, Henry Miller.

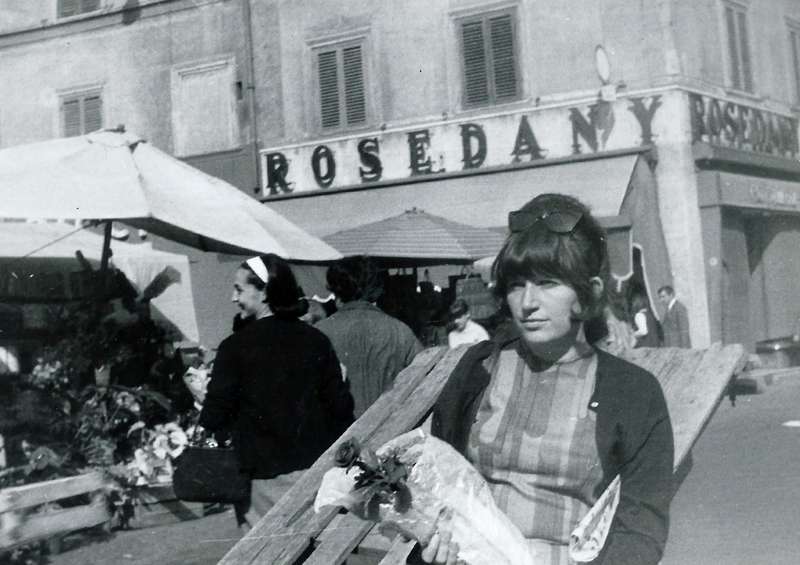

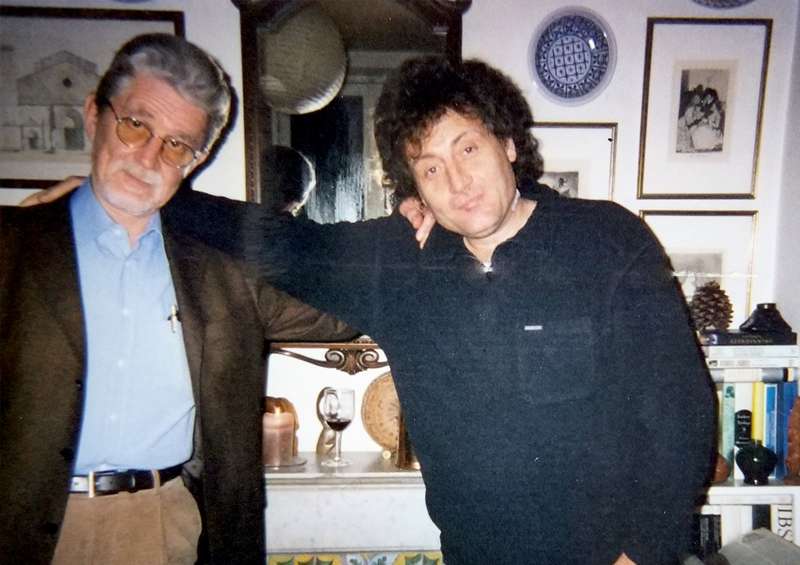

Two years had passed since dad had left Oregon. He was teaching English in Rome at the Centro Studi Americani where he met other Americans such as Shirley, first his girlfriend, then best friend and then our adopted ‘aunt’. Shirley came from Chicago. She was engaged to a Mr King, a very religious guy, but wanted to see Europe before getting married. She fell in love with Rome at once, forgot Mr King and stayed forever. She never ceased to marvel about by the golden light, the domes, the alleys, the frescoes and the statues of Rome, exclaiming “Oh look!” on every corner. Shirley rented a big house in Campo dè Fiori and my father moved in. There were ten rooms and a big terrace, but they didn’t have a shower. “We used a plastic hose on the terrace”. They did odd jobs at Cinecittà and taught English. There were painters, writers and philosophers, photographers and musicians, American and from elsewhere, in and out the house. They partied and enjoyed Rome’s lazy charm. Somewhere I have a newspaper clipping, an article in the local section about a group of bohemian Americans ‘revitalising’ Campo de Fiori in the 1960s. Shirley had two poodles that my father used to walk, a male called Dunque – with some masculinity issues: he wouldn’t lift his leg to pee, something dad tried in vain to teach him – and a female called Quindi. Shirley and my father loved the Romans’ vagueness (‘see you at about five o’clock’) and their warmth. Shirley’s favourite expression was ‘a meno che’ (‘unless’), a formidable pass in the world of fluctuating Roman rules. But my father mostly got mad at how some Italians ‘play it smart’ and skirt the law instead of challenging it.

One of his enigmatic teachings when I was growing up was this: “if you must steal, don’t steal from people, rob a bank, take a lot of money, and sign your full name”. I had no idea what that meant – maybe I had stolen a piece of candy from Emma. I like to think that his call for people to always stand up for their actions was a way of opposing his humanity to the faceless monster-bank that had taken the land from farmers during the Depression. More likely, however, it was simply an expression of a character trait my father developed towards institutions in general: a certain pride, combined with an innate and very strong sense of justice, of instinctively knowing what is right and what is wrong, and always stating up for it, openly.

He wrote letters to all kinds of authorities for any reason, all the time. It was mostly letters of protest – which I had to correct in Italian – to which he never received a reply. They were long, detailed, colloquial, and fictional letters. He began by introducing himself and us, the family – names, background, age, education, occupations, some character data, scenes from daily life, descriptions of the neighbourhood, anecdotes, various considerations and, finally, the problem. The correspondence with the building administration, which I found a few years ago in an old box, contains the story of my life. In asking for an old washing machine to be removed from the terrace, dad describes how my sister and I played with the water coming out of it, which we sent down the stairs. It’s a beautiful scene. The most elaborate letters, however, were the ones he wrote when he discovered constructions being carried out without permits in the neighbourhood: he took photos, wrote letters, filed complaints. But no Italian authority ever wrote back.

The only ‘authority’ he ever really loved was the New York Public Library. His stories about the New York library always began with the description of the two stone lions guarding the grand staircase leading up to the monumental entrance. The library’s logo is a stylised lion’s head which, at the age of 75, he tattooed on his forearm: a red lion’s head, the New York Public Library logo, just below the crook of his right elbow. Having returned to the States after his years in Rome, he was looking for work and when he had no money and nowhere to go he would spend hours in the library each day. No one kicked him out there.

He was furious at the American government for the war in Vietnam. In those years young men marched against the war and burned their draft cards in bonfires. But not him, he couldn’t simply be part of those protests: “what’s the point of burning your draft card, if the government doesn’t know you’re doing it?”. In 1973 dad tore up his draft card, put it in an envelope and mailed it to the chief of staff of the US army with a cover letter suggesting he go screw himself. The government replied. It ordered him to get his card reissued, to report to the authorities, to make himself available. His relatives forwarded the letters to him, because meanwhile he had moved to Canada. My father wrote back the same thing, again and again: go screw yourself. This went on for a while until the government sent some FBI agents to his relatives’ house. He got really mad and wrote yet another letter: “I’m in Canada, come and get me if you want me”. The government sent the Canadian police, put him on trial, and ordered him to leave the country. So he went back to where he had been happy, where the sun was shining and the weather was warm, where people called him ‘doctor’, where he bought tailor-made clothes to show off. He rented a place in Via dei Foraggi. The Grilli family and their two daughters, Linda and Cristina, lived next door, signora Franca, Viola and her husband lived downstairs, upstairs were Stefano and Antonio, the taxi driver; in the square there were Peppe who took us on trips to the lake, Lina and Alberto, the bar and the tobacco shop, in short, the neighbourhood, his home, his kingdom, that he never left, where he always knew and greeted everyone getting all his accents wrong. In Rome he would meet a beautiful English girl, a bit shy but “very smart”, he said, and he would find a good job at ANSA – after all, what else could he have become with his passion for long and detailed letters of complaint, if not a journalist? My father was a storyteller, he would talk for hours and hours and hours. You just couldn’t stop him. I wonder where I got my love of writing. But that’s another story.

This text was in part written for the book “Abitare Stanca” by Sarah Gainsforth (Effequ, 2022)

Gary Patrick Gainsforth memorial 2022

Gary Patrick Gainsforth memorial 2022

Email: contact@gpgainsforth.net

Privacy policy

We donated the funds collected by friends to Emergency, for a future without war.

We donated the funds collected by friends to Emergency, for a future without war.

Emergency is a humanitarian NGO that provides free medical treatment to the victims of war, poverty and landmines.

Gary Patrick Gainsforth memorial 2022

Email: contact@gpgainsforth.net

Privacy policy